Welcome to the Wildlife Pathogens Lab

We study host-pathogen ecology and evolution including links between hosts, vectors, pathogens, and the environment. As the world changes due to climate change, changing species distributions and introductions, environmental contamination, etc., so do these host, vector, and pathogen associations. We love to be in the field and our research takes us across the forests, fields, lakes, and ponds of Vermont, across the northeastern US, and further abroad. Our research includes broad multidisciplinary collaboration and the combination of field, lab, and analytical work. To learn more about our major research areas please read on below. To see who we are click on the “Team” tab above. Thanks for visiting!

Pathogen discovery

Discovery of pathogen species and genera from wild vertebrate and invertebrate vector hosts across the globe. Everywhere and in every species we look we find something new.

Pathogen spillover

Many vector-borne pathogens readily host switch and spillover into naive host taxa including collection animals at zoological parks, non-native species, species of conservation concern, and northerly distributed wildlife taxa. Disease and death often occur after pathogens spill into novel hosts. Here we investigate pathogen spillover into new host populations and species and the factors involved.

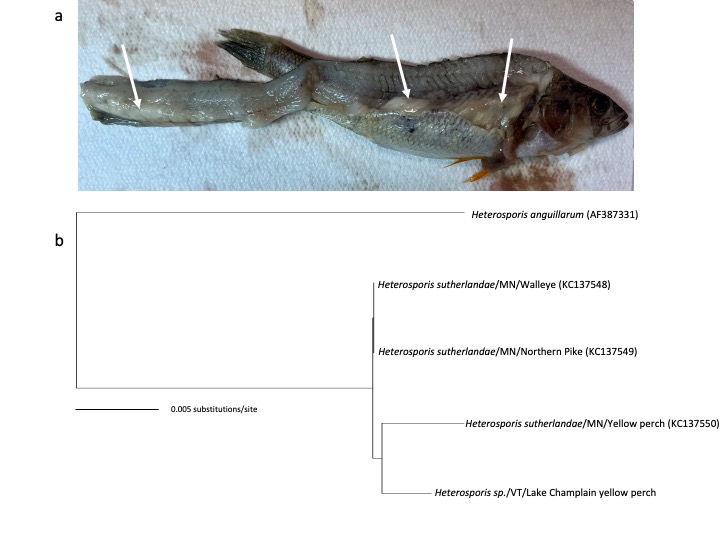

Emerging fish pathogens in Lake Champlain fish

Coupling visual inspection of skeletal tissue and gene sequencing, we are investigating the geographic distribution of Heterosporisis parasites in yellow perch in Lake Champlain. This parasite, which creates freezer burned lesions in skeletal tissue, showed up in Lake Champlain about ten years ago. Our work to date shows a spotty distribution of this enigmatic parasite and possible correlations with fish health.

Connections between contaminants and disease risk

As human activities spew off a diversity of pollutants, do these environmental contaminants render hosts more susceptible to infectious disease? We investigate the relationship between pollutants and infectious disease risk in species of birds subjected to high levels of contaminants (mercury and lead) including Saltmarsh Sparrows, Common Loons, and Bald Eagles.

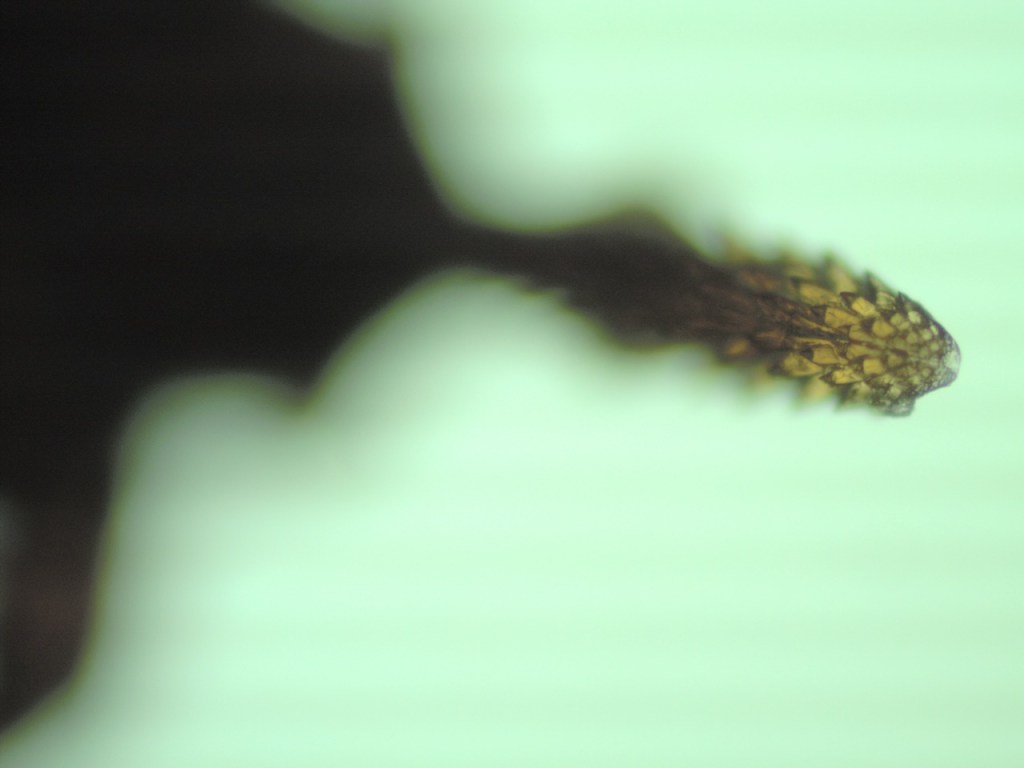

Time for ticks

Tick species continue to march northward due to climate change and landscape modification and present novel agents of infectious disease to more northerly distributed wildlife species (and humans). We investigate the zoonotic pathogens that invasive tick species are infected with as well as habitat factors that may impact infection risk. Shown here is a picture of a black-legged (deer) tick hypostome at high magnification. This mouthpart is injected into the host and used to suck blood.

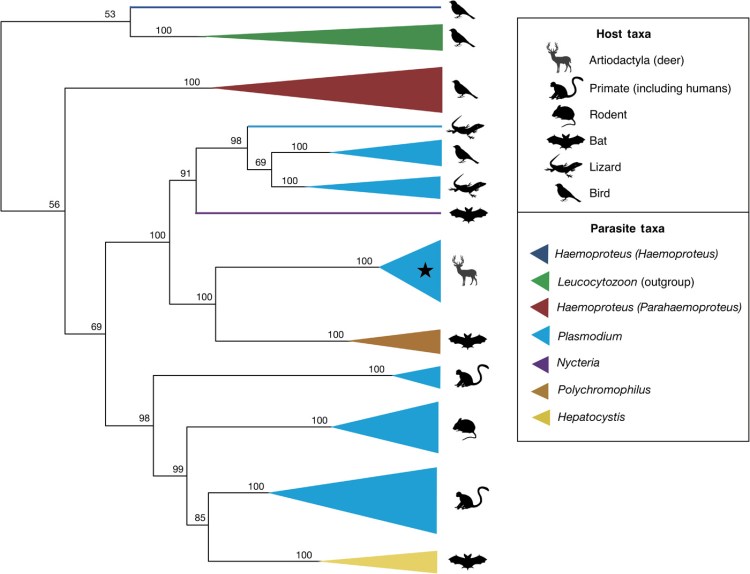

Understanding pathogen diversity

Through the use of traditional light microscopy and genetic data, we reconstruct the relationships between wildlife pathogens (how closely related they are to each other) as well as track their evolutionary history and diversification over time including the coevolution of hosts and their parasites as well as the importance of host switches into new vertebrate and invertebrate vector hosts.

Common Loon Malaria

Yes, Common Loons get malaria and recently have been found to die from malaria. Common Loons are an ideal study species to study malaria as they are icons of the northern wilderness, historically have not been found to be infected with malaria parasites, and are oftentimes found when deceased. Through broad collaboration with loon biologists and wildlife veterinarians across the US, we have documented a diversity of malaria parasites from the species. We have also discovered disease and death associated with malaria parasite infection in Common Loons in the Northeast.

Cervid pathogens

Cervids including white-tailed deer are chock full of vector-borne pathogens that are moving northwards and expanding their geographic range due to climate and landscape change. We rediscovered the malaria parasites of white-tailed deer and continue to study these parasites as well as other life threatening vector-borne pathogens of deer and other cervid species including moose in the northeastern United States.

There are so many things you can learn about. But… you’ll miss the best things if you keep your eyes shut.

DR. SEUSS